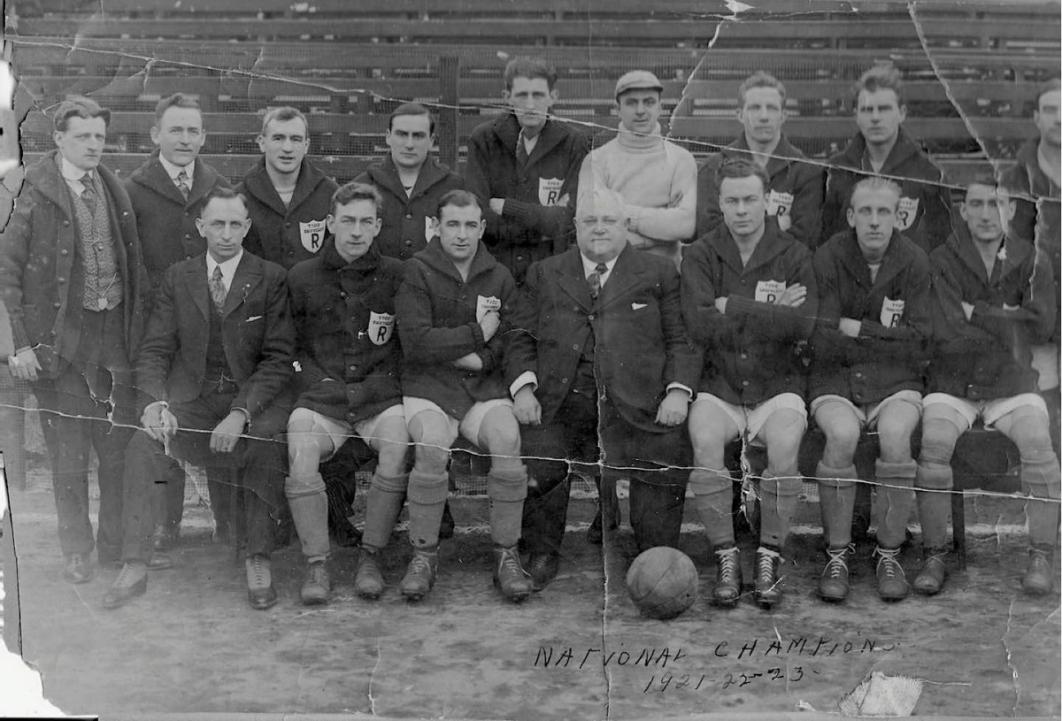

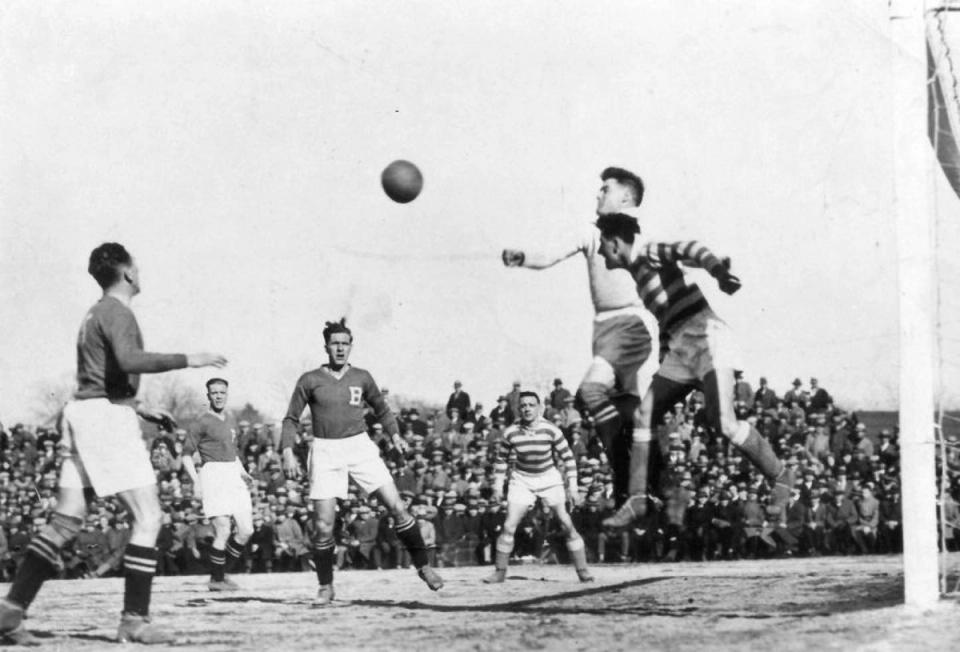

Global Pandemic, World War & the 1919 Open Cup

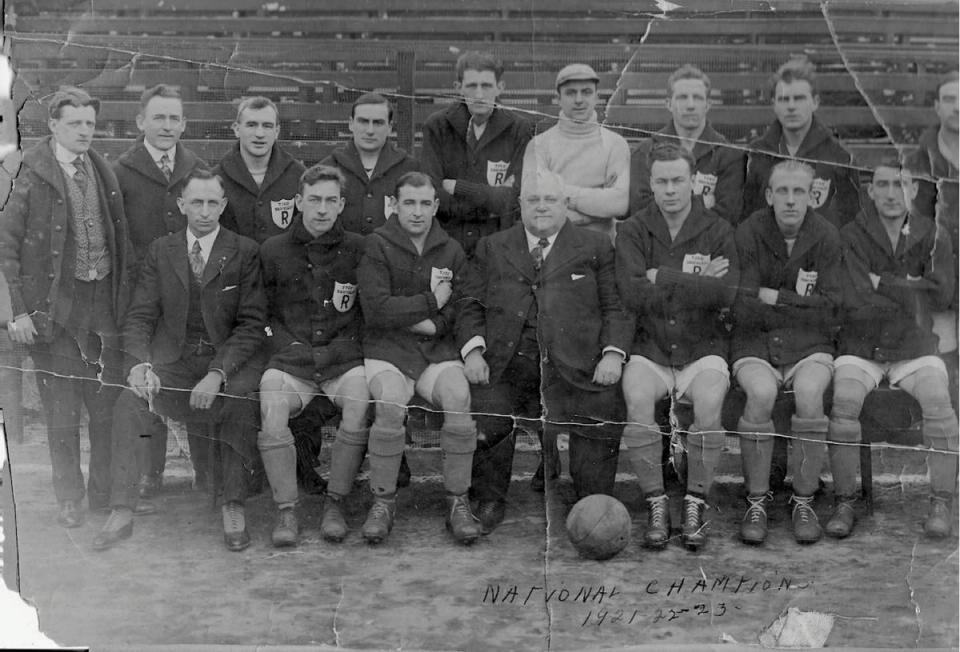

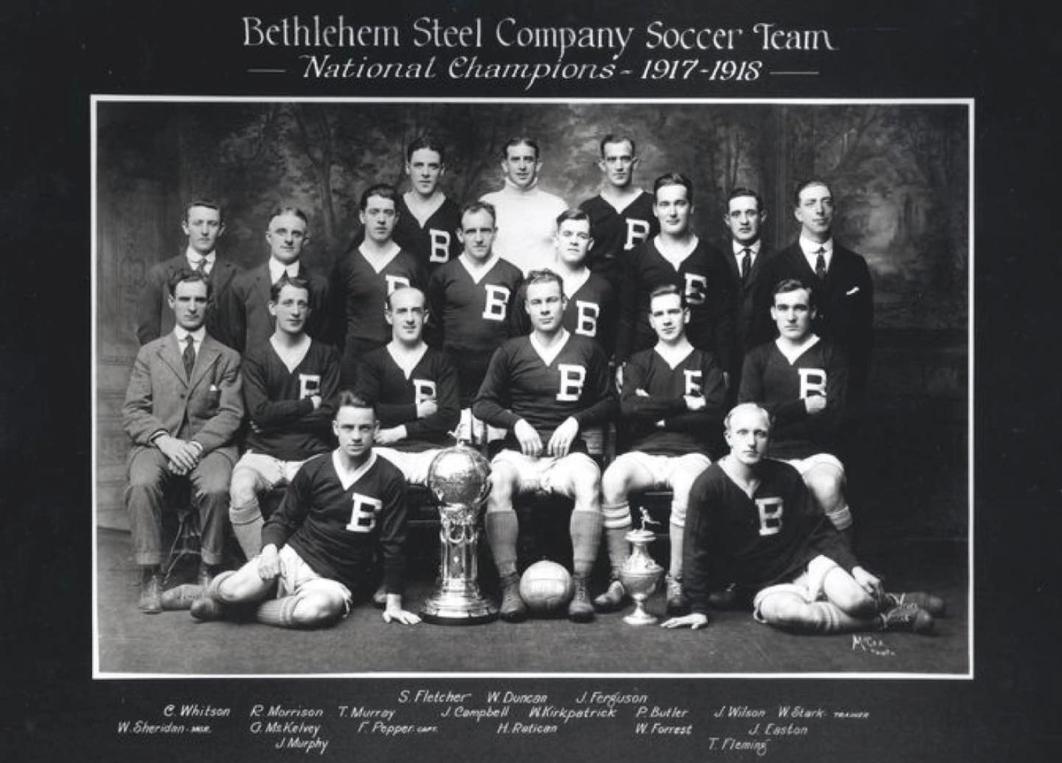

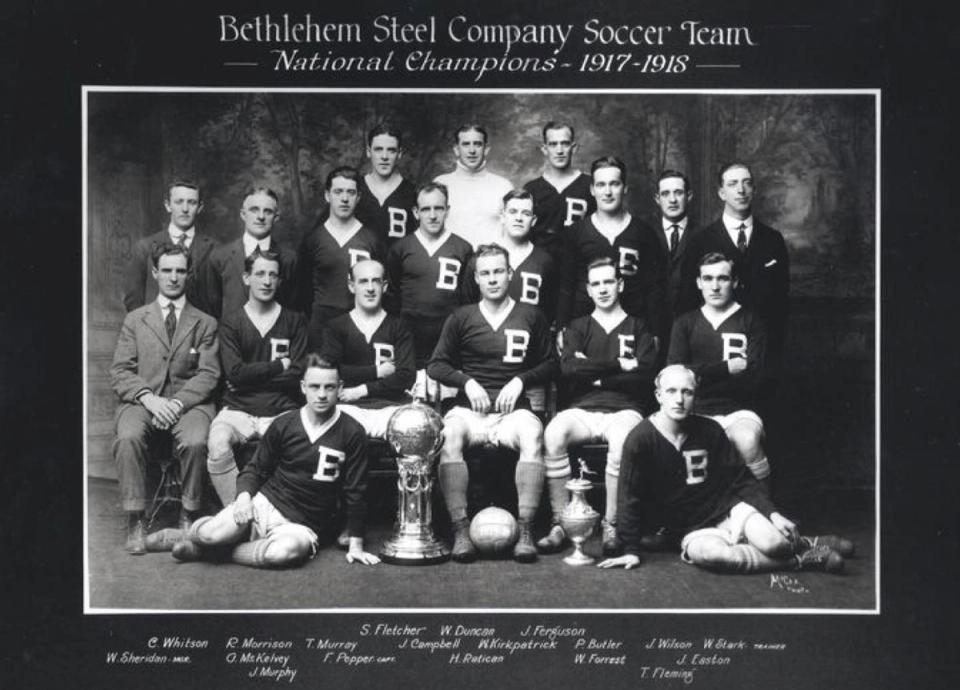

The 1919 U.S. Open Cup carried on to see Bethlehem Steel crowned champions for a fourth time despite a global pandemic and a raging world war.