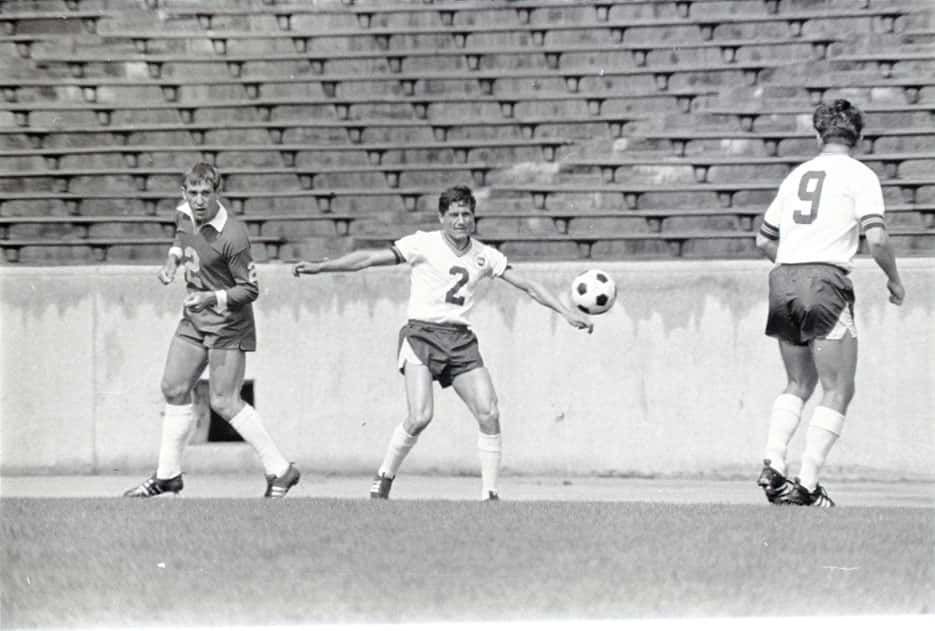

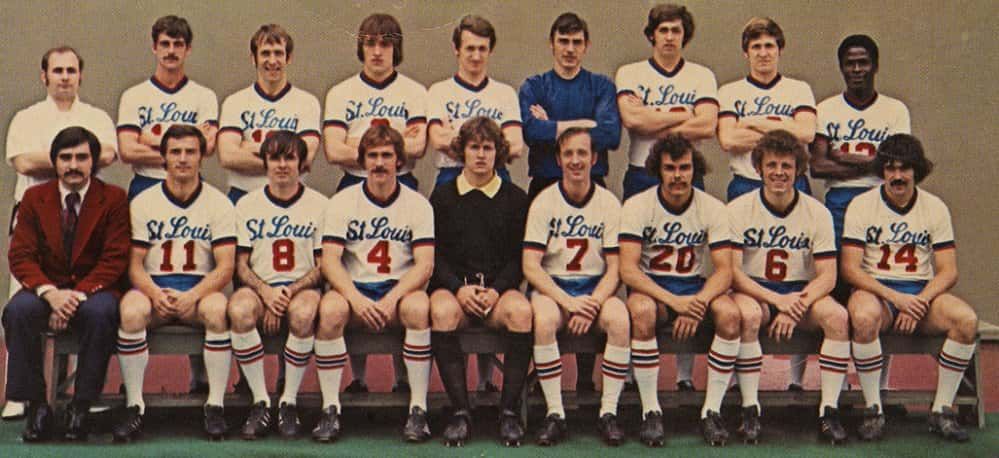

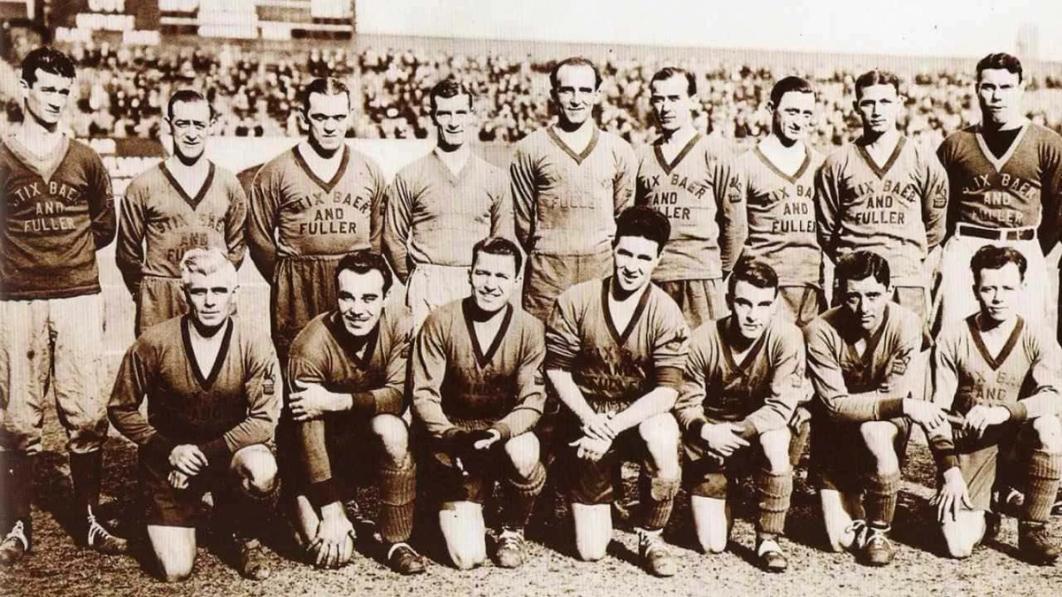

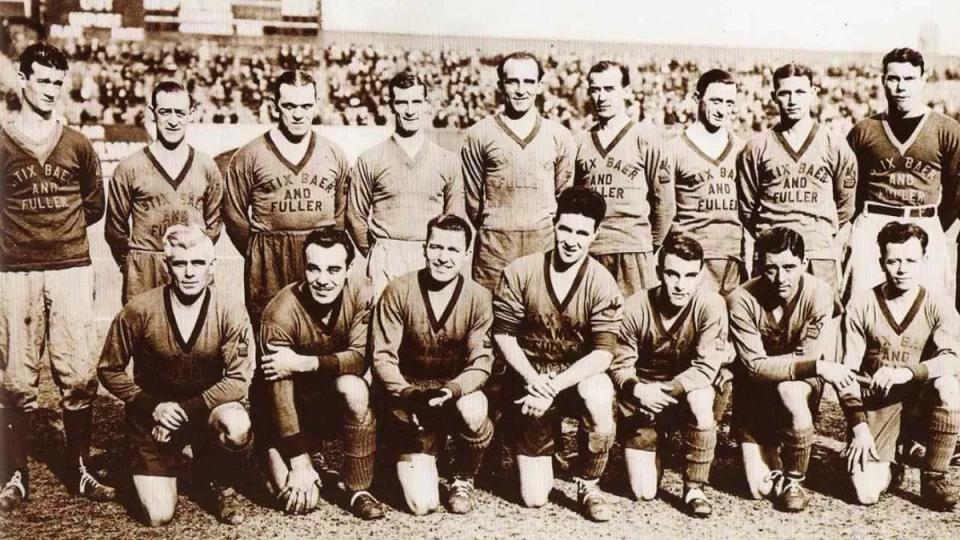

Open Cup Rewind: Chicago & St. Louis – A Tale of Two Cup Cities

With Chicago Fire of Major League Soccer squaring off against USL Championship side Saint Louis FC in the 2019 Fourth Round, it’s as good a time as any to look back at the rich Open Cup histories of these two great cities.